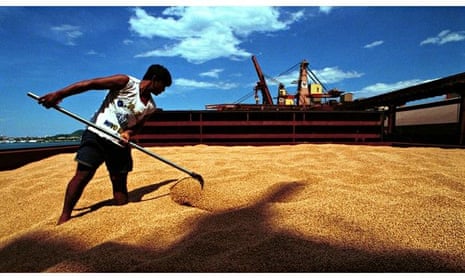

Patterns of trade and the distribution of market power in the global economy are shifting – rapidly. In the past, most trade in agricultural commodities occurred between the countries of the global south (sites of production) and the countries of the global north (sites of consumption).

But, in recent years, the volume of south-south trade has increased significantly. Today, some of the environmentally most problematic crops such as soya and oil palm are predominantly traded amongst southern countries. With a total import volume of 63m tonnes in 2013, China is now by far the largest buyer of internationally traded soya, and India’s share of the global palm oil trade is estimated to have reached 20% (China 16%, EU 14%).

The booming demand for soya and palm oil in emerging markets has further fuelled agricultural expansion, deforestation, and biodiversity loss in producer countries such as Brazil, Indonesia, and Malaysia – creating a new sustainability crisis in the global south.

The mechanisms of change

Over the last two decades, voluntary standards systems have emerged as an important mechanism in addressing the negative externalities of transnational production, as they are less constrained by national borders and rules of the international free trade regime than public regulators.

In agriculture, private sustainability initiatives are now an integral part of the emerging global governance. WWF’s roundtable initiatives in key agricultural sectors such as palm oil, soya, sugarcane, and cotton are a good example. Different from organic labels and the fair trade movement, which focus on price premiums and niche markets, they are mainstream platforms designed to shift the entire sector toward more sustainable practices.

According to Jason Clay, WWF’s senior vice president of market transformation, there are 15 key agricultural commodities responsible for the majority of the sector’s environmental impact. Of those commodities, 70% are under the control of a limited group of 300–500 companies.

Against this background, WWF seeks to engage the top 100 influential companies which between them control 25% of the trade in these commodities in its roundtable initiatives. By doing this, the NGO hopes to significantly reduce the environmental impact of agricultural activity.

Ultimately, the model’s success rests on the market power of big brands. Incentivised through reputational and regulatory pressures as well as demand for sustainable products in northern consumer markets, they engage in private initiatives and implement their standards in their global supply networks.

Can voluntary standards help?

Unfortunately, in their current form, voluntary standard systems are not well equipped to deal with this sustainability crisis in the global south. For the most part, they continue to operate on the basis a north-south trade model, trying to leverage the market power of northern consumers and big brand companies.

However, the effectiveness of this model is increasingly undermined by the changing nature of agricultural trade. India and the palm oil sector are a good example. Earlier this year, the Centre for Responsible Business (CRB) published a study examining the market uptake of “sustainable” palm oil in India. It found that Indian companies lack incentives to source sustainably.

The industry’s major voluntary scheme, the Roundtable on Responsible Palm Oil (RSPO), has very little traction in this, the world’s largest import market. In 2013, India imported a total of 8.67m metric tonnes of crude palm oil – mostly from Indonesia and Malaysia – of which only 144 tonnes were RSPO certified (0.0016%). For obvious reasons such figures are a problem for an initiative created to protect the rainforests of Sumatra and Borneo.

Why does the model not work?

The answer lies in the nature of south-south trade and the specific characteristics of these markets. In the Indian context, two factors seem significant. Firstly, brands only play a minor role.

According to the study conducted by CBS, palm oil in India is sold primarily (89%) in loose form and only a very small percentage (11%) enters the market in the branded and packaged form. Secondly, palm oil in India, also termed poor man’s oil, is highly price sensitive. As a result, companies have very small profit margins and therefore, in the current market environment, pricing takes precedence over sustainability concerns. This means that in the south-south trade setting described above key conditions necessary for the RSPO to gain market traction are currently missing.

This might change over time. The market share of branded companies – Indian or foreign – is likely to increase as the country continues on its development path. Also, the growing middle class in India will become increasingly aware of sustainability issues, creating local demand for sustainable palm oil and other agricultural products.

Unfortunately, by then, it might be too late for the rainforests in Sumatra and Borneo, which are vanishing at a breathtaking speed (the deforestation rate in Indonesia is estimated to currently amount to 1.17m hectares per annum). Therefore, we urgently need new models and strategies to address the south’s sustainability crisis.

Philip Schleifer is a Jean Monnet Fellow at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute. He holds a PhD in International Relations from the London School of Economics and Political Science

Read more stories like this:

- Why zero deforestation is compatible with a reduction in poverty

- Understanding the origin of products is key to ending supply chain scandals

- Advertisement Feature: Giving smallholders a seat at the table

The supply chain hub is sponsored by the Fairtrade Foundation. All content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled advertisement feature. Find out more here.

Join the community of sustainability professionals and experts. Become a GSB member to get more stories like this direct to your inbox

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion